Julian Irlinger

Europe Divided Into Its Kingdoms

“The Canon T70: combining optical, mechanical and computer engineering that sets it apart from any camera you have ever seen or handled.” This is how the SLR camera, first appearing on the market in 1984, which Julian Irlinger used to shoot the self-developed negatives of the gelatin silver prints which hang on the walls of the gallery, was described. Once available as a milestone among amateur cameras for the hefty price of 750 DM, it soon became affordable for every hobbyist photographer when the autofocus camera was invented – including Irlinger’s mother. She not only preserved private moments with this clunky apparatus, but also constructed a family history in the form of a family album extending over years as a mirror and place of certainty.

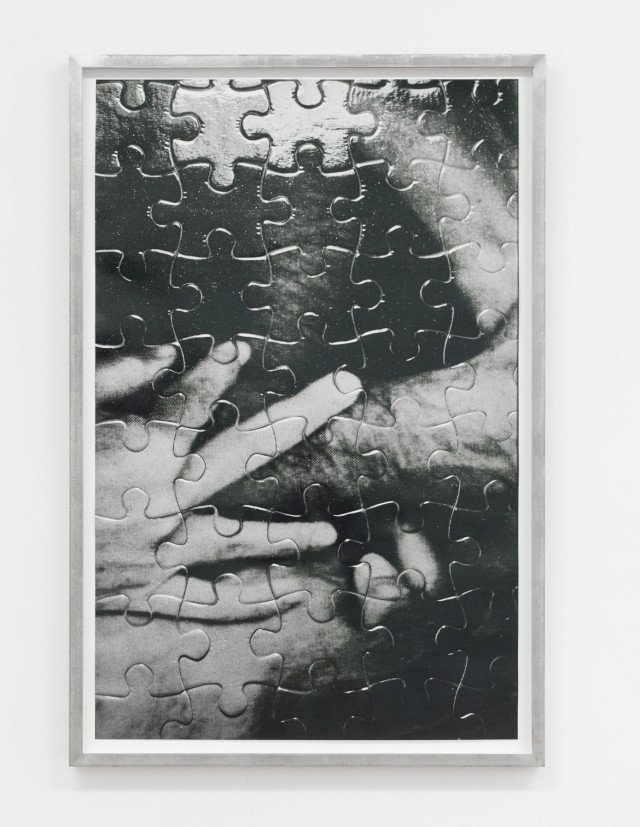

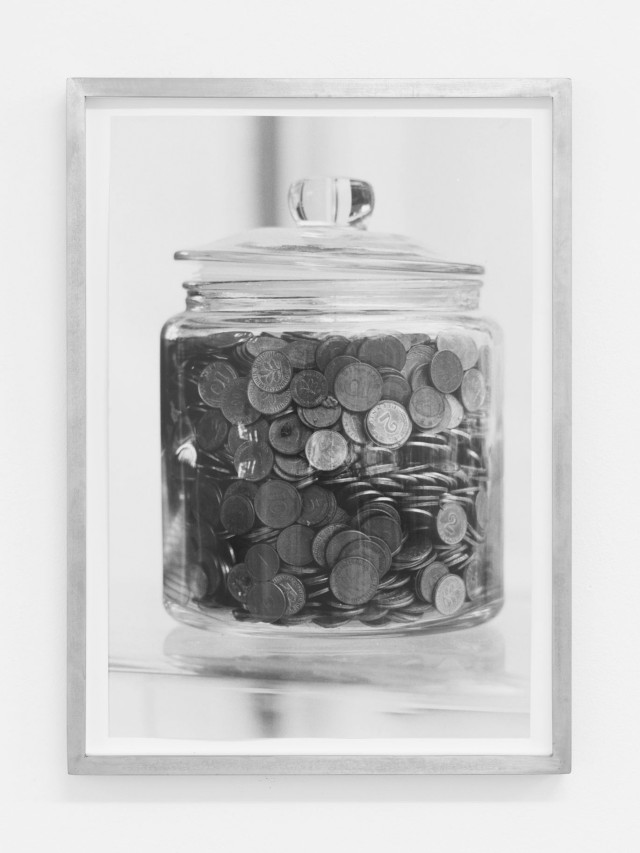

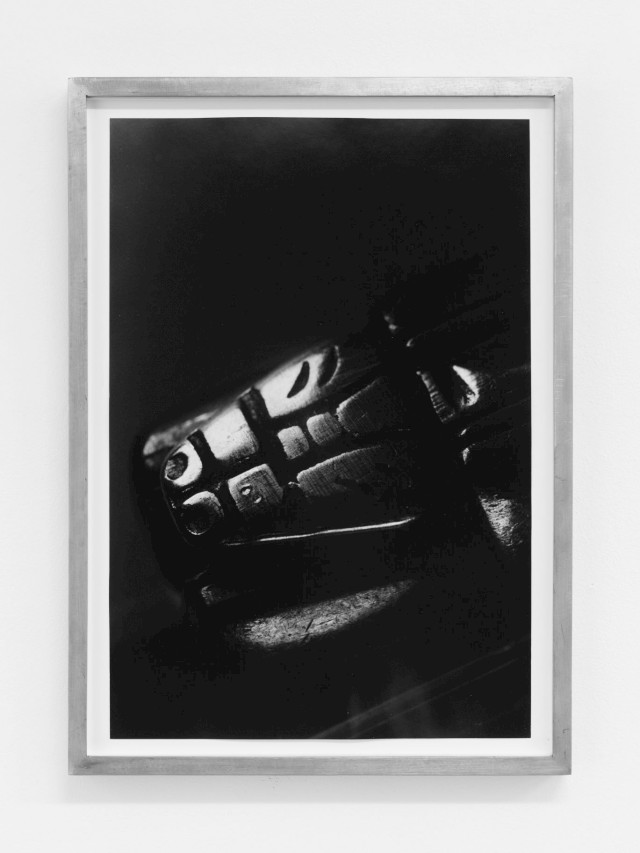

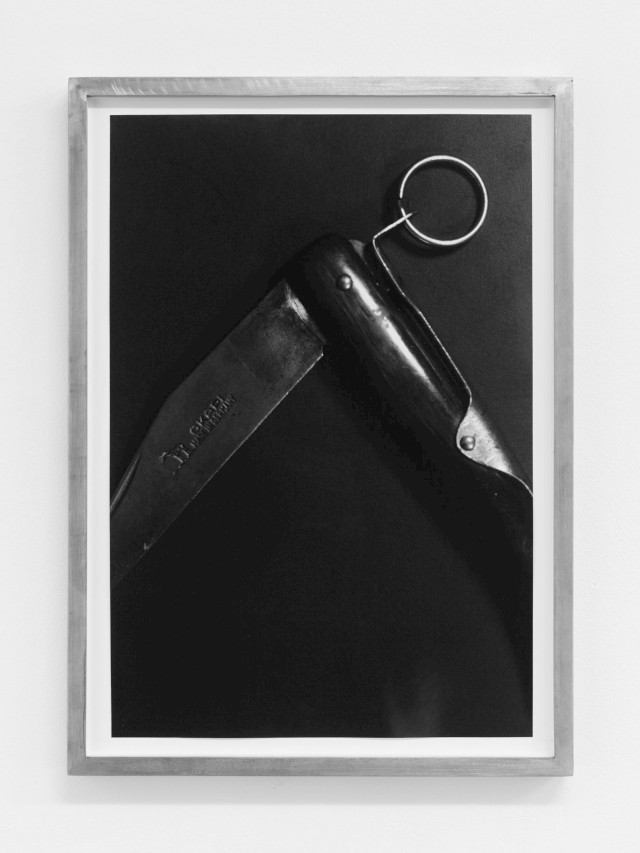

Accompanying Irlinger since his childhood, this sentimental object has flourished into memorabilia of its own, used for ten years to capture things, conventional matter and its surroundings. The objects depicted in the photographs on view in this exhibition share this realm of memorabilia and recollection.

With its micro buttons, LCD screen and “intelligent computer technology,” the T70 camera was like no other, a child of the 1980s computer age, and today can be pinpointed as resting on the precipice of the post-analog and pre-digital netherworld. Such a terra nullius into which one looks back into the future, so to speak, predicted by Katsuhiro Otomo four years before his cyberpunk anime classic lm Akira was released, appears in the debut commercial of the Canon T70, which serves as the flyer for this exhibition:

Two anime figures dressed in retro-pop chic – on the left a cropped woman in a turquoise bodysuit, on the right a man in a squeaky red leather jacket with a diabolically sinister gaze directed at us, while the camera floats like a crystal ball in his hands. Behind them, a tracing-like copy of Peter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel in black outlines recedes into the distance like a phantom ruin.

As a critique of human hubris, the unhinging of the original unity of people and languages manifests itself in this Bruegelian construction with impossible foundations, which seem to have already laid themselves to waste.

It is therefore no mere coincidence that reproductions of Bruegel’s painting once embellished the walls of computer labs from the 1950s onwards as a dystopian leitmotif in the face of planned uncontrolled growth. Attempting to rectify the aftermath of the construction of the tower with the “unity through formalization” principle ought to serve to finally concoct a langue universelle in information systems. In this telematic society, it was not the immediate gaze that was meant to feed us with image production and stimulate discourse, but a medial, apparatus-directed gaze: where Flusser notoriously positioned photography at its beginning.

Ultimately, those frozen capitulations into the present as leitmotifs, like Bruegel’s painting, envision the dialectic of the polysemic word aufheben (to keep or to remove) in the image-making process between the present and the past without ever declaring reconciliation: On the one hand, preservation, to keep the traces of the past for the purpose of remembering and retrieving. On the other, erasure, to suppress and forget unwanted truths. This dialectic of preservation and erasure also applies to prevailing exegeses of a myth of “plurality as punishment,” as the tower of Babel demonstrates, as well as the proto-history of loss that embraces a nostalgic longing for a forsaken imagined unity – a longing as an “imagined homecoming itself.”

Svetlana Boym distilled this relationship to the past, to the imagined community, to the homeland, to one’s own self-perception into “restorative” or “reflexive” nostalgia. While the former tries to revive the past as rigorously as possible – and in doing so, runs the risk of rebirthing the “nation” as a conceptual framework – the latter feeds instead on the soothing longing that loss creates, which acknowledges that the process of remembering is imperfect: the past can never truly be reconstructed.

A black and white photograph can be precisely staged and equipped with that nostalgia to represent an idealized past that de es the present. The luminous imprints produced with the help of an analog camera – such as the T70 – might trigger authentic traces of presence, so-called indexical effects that massage the very authority of a photographic image. This is a photograph that often comes with forensic assumption like “that’s the way it was,” this is where it was and that its imprints are analogies of reality, causally (and actually magically) linked to its object.

However, to misconstrue the photograph as the primary vehicle of expression and communication would be myopic, since it can stand in equal and sometimes in conflicted partnership with the written word even if it’s mostly elsewhere: titles, labels or even this exhibition text – examples demonstrating that what we see, and how we recognize it emerges from a combinationatory process. This “third something,” as Eisenstein called it, does not only serve to nourish or topple the articulation of a nostalgic “trace,” but moreover reminds us to revise practices of its reading.

Thus, one might ask in our present moment: How can a supposedly dewy-eyed black-and-white photographic image negotiate its discursive network and relationships to the past, its subject, the apparatus, the written word and the represented object in a deliberately unfinished operational manner? How can it even unfold something like a utopian potential in nostalgic acts of consumption and function as a prospective talisman for its own blind spots?

Elisa R. Linn

2021

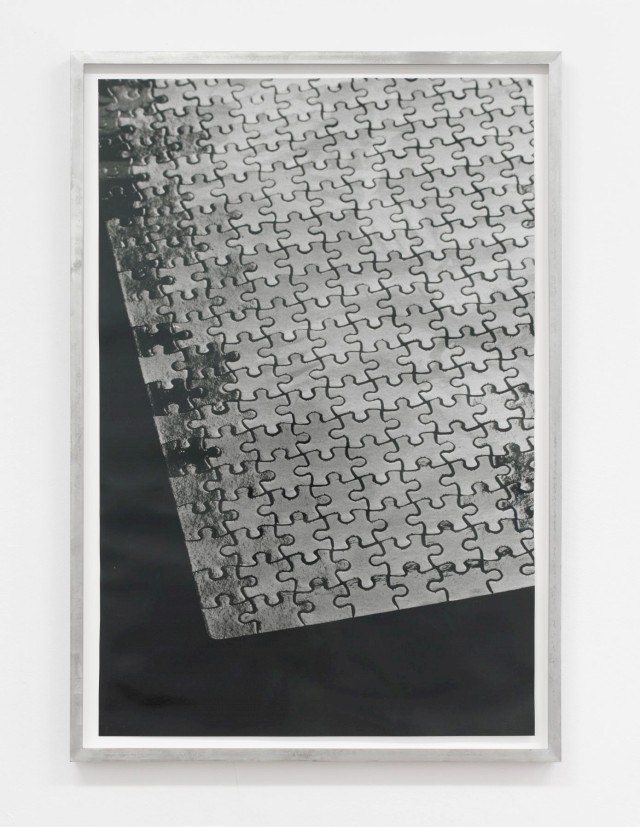

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

100 ×66 cm (print)

107,5 ×74 cm (framed)

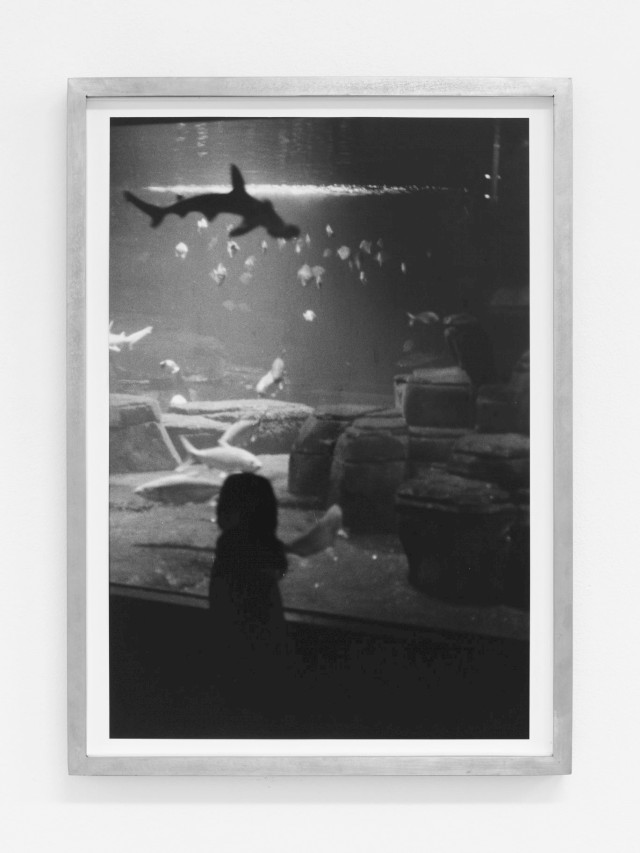

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

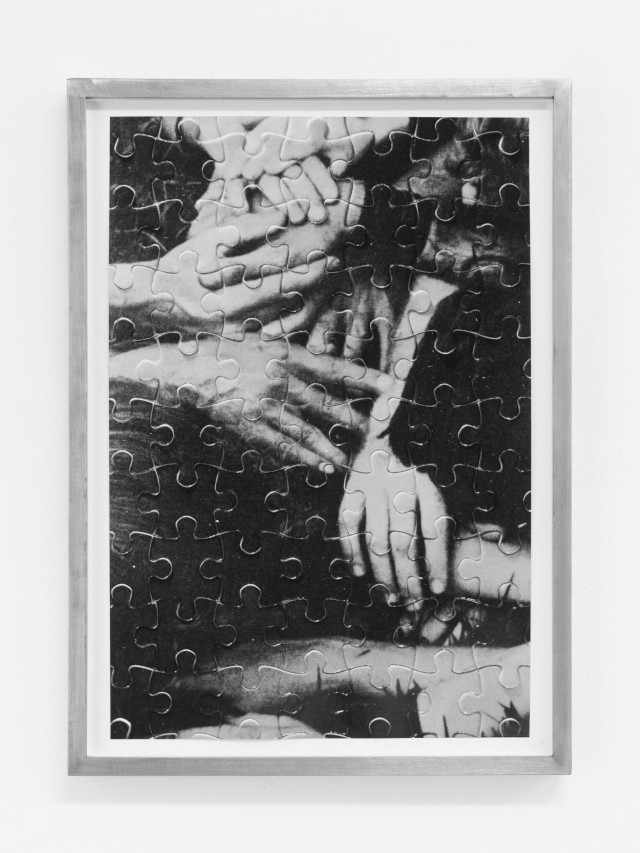

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

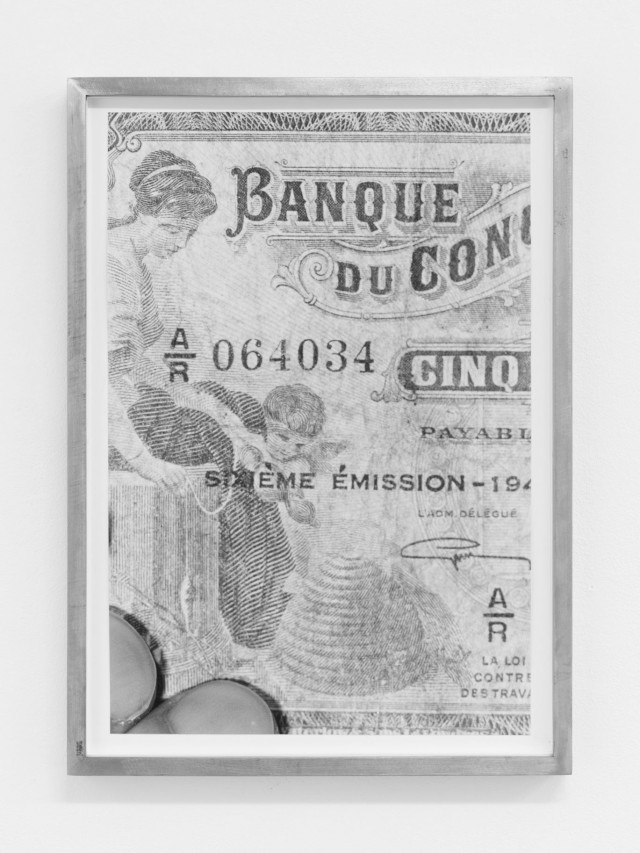

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

100 ×66 cm (print)

107,5 ×74 cm (framed)

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

2021

Gelatine silver print, custom made steel frame

50 ×33,5 cm (print)

55,5 ×40 cm (framed)

View exhibition booklet (PDF)